The Inner Game of Screenwriting with Christian Lybrook

Jake: I have a special guest today, Christian Lybrook, who is one of our ProTrack mentors at Jacob Krueger Studio.

I’m especially proud to have Christian here because Christian came up through our program. He’s an extraordinary writer. He has produced and directed his own work, he’s managed to maintain a career as a writer from Idaho! ( we won’t tell anybody, Christian) And he’s also just a sensitive human being with incredible emotional intelligence, towards both his characters and the writers that he mentors.

We’re going to be talking about the inner game and the personal side of becoming a writer today with Christian. Welcome, Christian, thank you so much for being here.

Christian: Thanks for having me. As you know, one of my favorite pastimes is chatting about all things screenwriting. Happy to be here.

Jake: Tell us a little bit about your journey as a filmmaker. What has that looked like? And what do you think was most important thing in making the transition from being someone who is dreaming of doing this to being someone who’s doing it?

Christian: Yeah. Great question. You know, when I think about my journey as a screenwriter, everybody knows that every journey is different. And anybody who’s listening to the podcast, you’re going to have a different version of what your story is.

But I think it’s helpful to talk about these stories, because they can be illustrative of the things that we have faced and the things we have to overcome. I wast somebody who didn’t go to film school, I wasn’t somebody who grew up in the business, I didn’t grow up in LA or New York. And for a long time, I was always interested in film and screenwriting. But I didn’t think that I could do it because I didn’t know how to get into the industry.

I grew up on the East Coast. I was born in Massachusetts and moved around a lot. But by the time I was kind of pursuing writing, I was in grad school in Alaska, which is about the farthest away you can get from LA and still be in the United States.

I took a screenwriting class as I was getting an MFA in Creative Writing. And I was focused on fiction, primarily because, although I secretly wanted to be a screenwriter, I just didn’t know how to complete that training. And I took one screenwriting class, and that immediately ignited something in me, but I still was literally thousands of miles away from the industry.

And living in Alaska, and trying to make it as a screenwriter just seemed like a ridiculous ask. So I stayed focused on prose, and eventually, I followed a girl to Idaho. And that’s where I am today.

One of the nice things about Idaho is it’s a very small place. And you could do things and meet people much more easily. It’s a very small community. You meet one person and they’re going to introduce you to the next person, and the next person.

But it was also at this time when technology was being democratized. And for the first time, if you owned a video camera and a computer, you could make a movie. And that was really my entree into taking a stab at this stuff. Because I didn’t have to be in LA. I realized I didn’t have to be surrounded by pros, I could just make it up as I went along.

The first short film I made was with some buddies. None of us had training, none of us had experience. And we all thought, how hard can it be?

It turns out, it’s really fucking hard.

But it was a great introduction. And there are elements of it that I fell in love with. I taught myself how to edit. And I love that process of the puzzle coming together visually, and cracking these problems and being able to insert a shot, and suddenly, the whole thing came together.

And the editing process provided a new light on the writing process, because I got to see things from start to finish. We were directing the things that we were writing. They were just goofy little sketches, but it kind of set the stage for me.

And that’s when I started to say, maybe I want to do this more seriously.

I had this short film that I wrote with some of my buddies, and I directed it, and it was just this creepy little ghost story. But it was the first time that the images I’d seen in my head were actually rendered on the screen in a way that really mimicked what I saw. It felt like a film, not just a video. And I went, Oh, maybe I can do this.

I’ve spent a lot of time just working full time and trying to make a go of this stuff. But there was a huge piece of it that I didn’t have yet.

You talked about emotional intelligence. I’ll be honest, I don’t think I’m naturally gifted in that way. I’ve had to work really hard at it.

Because my natural inclination is to take my emotions and to take the things I’m ashamed of and the things that I fear and the things that I don’t want people to know and keep all of them at arm’s distance.

I don’t want anybody to see that stuff. Why? Because I’m terrified of being judged. And I couldn’t face that. I didn’t realize it earlier in my journey. I thought I knew how to write characters. But I was never going deep on them. And there were elements of things that were working, but I couldn’t feel it. I couldn’t figure out what I needed to do.

Fast forward a number of years, my mother had died. She died of cancer in 2017. There was a whole lot of family drama that was happening during that time. And I knew that I needed to write about this stuff. But I also knew that I couldn’t write about it and still keep all that emotion, and all that grief, and all the shame and everything else– I couldn’t keep it at arm’s length. I had to let it in and I had to let it out onto the page. Otherwise, people were going to read it and realize that it just felt surfacey and fake.

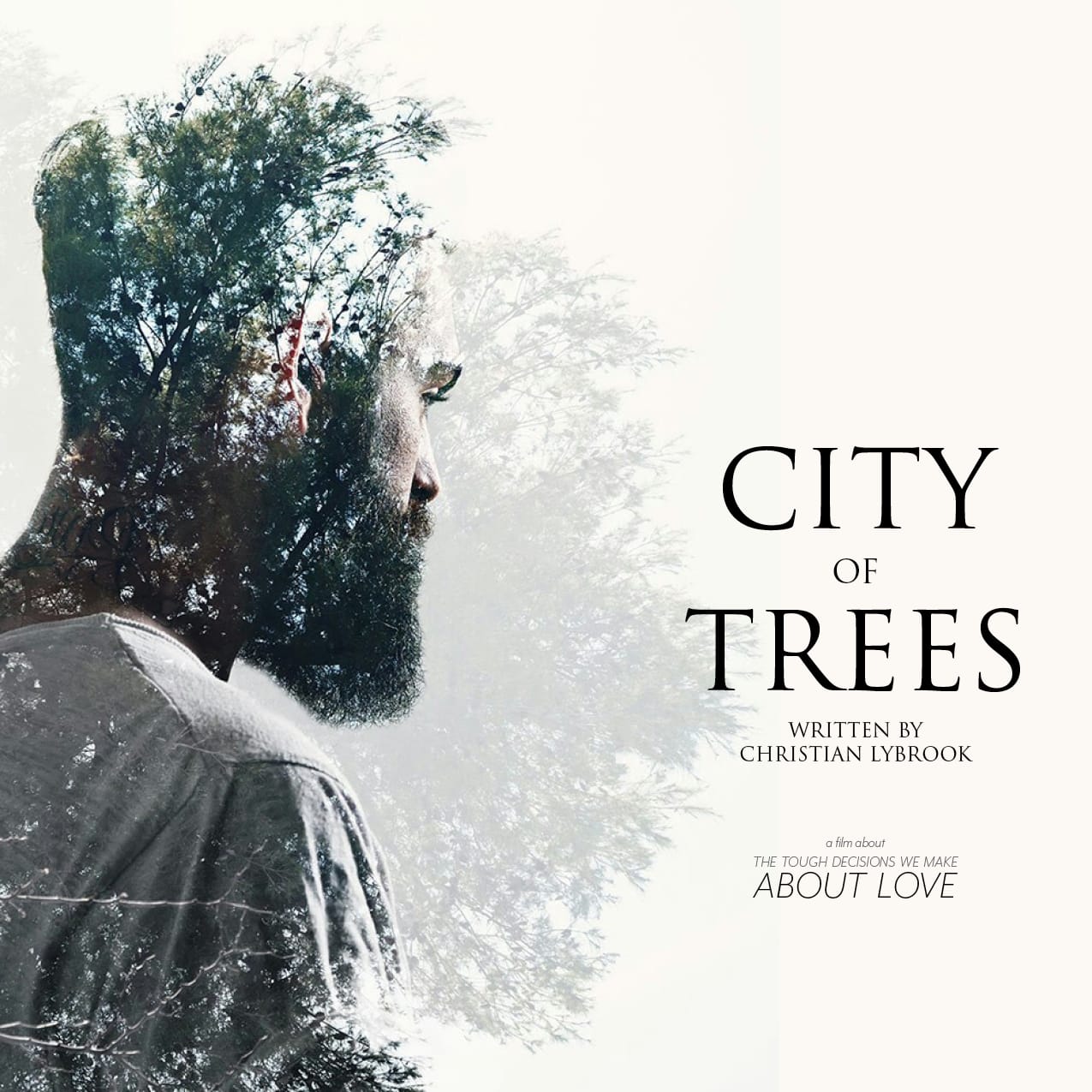

It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do, because I’m terrified of people seeing the real me. And as I went through the process, that was the script City of Trees, which is a family drama about a guy who’s got to come back to his hometown when he realizes his mother’s dying.

And I wondered, how is this movie going to be different than every other movie that feels like this? That’s when I started to realize it was how I was telling the story. It was elements of structure and the choices I was making. But it was also being very honest and vulnerable with my own experience, and the things that I’m totally insecure about, and putting those on the page.

Even though people have said this to me a million times, when I was in my MFA program, Charles Baxter, who’s a novelist, had come up, and he’d read one of my short stories. I honestly don’t remember what we talked about with the short story. But I do remember him saying at the end of it, Christian, if I could give you one piece of advice, write what scares you.

And I was like, right, write scary things.

Because I was an idiot. Because I knew what he was saying, but I didn’t want to face it.

That idea of writing what scares you is what I finally did in City of Trees, because that’s what everybody wants to know, that they’re not alone with these feelings of inadequacy, these feelings of shame, of grief, of all the things that we don’t want to talk about.

As I started to put those on the page, I could feel– not necessarily a weight being lifted off me because I still carry the stuff around, it doesn’t go away– Energy is neither created nor destroyed. It’s only changed. The energy that I had, it’s not that it went away, it’s not that it was eradicated, but it transformed into something different through the writing process, and through embracing all the things that I was terrified of.

It was the first straight-up drama I had written, partly because I think I realized that I was afraid to face this stuff. And I knew that I would have to. And that script went on to do a lot of great things for me.

One of the things it did is it got an invitation to go to a screenwriting residency in Switzerland called the Plume and Pellicule. They had consultants from all over the world. And I was meeting with one of them, and he’s Cuban, and he doesn’t speak English as his native language was just translated.

And we’re at the end of our conversation. And the translator says, Oh, he was asking how long it took you to write the script. I thought about it, and I said, 48 years.

And I wait for her to translate. Then he laughs, because he understood that this was a story that was a lifetime of accumulation of events, of experiences, of emotion.

I think everybody has a version of going through, here’s my idea of what a screenwriter is. Then, where the rubber meets the road, here are the things that we really have to do.

Jake: I’ll never forget my introduction to Christian. My good friend, Philip Gilpin, who runs Catalyst, which back then was called ITVFest, calls me up, and says, There’s this guy, and he keeps winning. And he’s incredible. But he needs someone to push him over the top, and I need you to make it possible for him to come to your retreat.

We were doing retreats in Costa Rica at that time. And Christian shows up at the retreat, and he’s the first one to arrive. We walked down to the beach together, and we’re having this really cool conversation.

Then Christian kind of looks at me– and Christian might have told you he’s a guy who doesn’t have a lot of emotional intelligence, but it’s not true– he kind of looks at me and with brutal honesty, he says, I don’t know exactly why I’m here. Because I don’t believe in any of this shit.

I said, Christian, that’s okay. You don’t have to believe in any of this shit. Let’s just try some shit and see what works.

Then we went swimming. And it was one of my favorite introductions ever to a writer. Because it’s really rare that somebody is that blunt and honest with you. And I think a lot of people have had that experience where they’ve had a class that hasn’t helped them. They’ve had a teacher that hasn’t helped them. They’ve had someone teach them some kind of formula that hasn’t helped them. And they start to wonder, is there anyone that I can depend on?

Christian: In my defense, the journey from Idaho to Costa Rica is like 27 hours. If you were in New York, it’s actually a pretty quick trip. I got there, and I was delirious. Then we had that crazy van ride through the jungle… I’m glad that you saw opportunity and honesty in my bluntness. I think I was just delirious. But there was obviously some truth that I was speaking.

I had been laid off from my corporate job. And I knew there was an opportunity in front of me.

But it was also terrifying, because I didn’t realize this at the time, but it’s like the Admiral of the Navy arriving in the foreign shores, and he says, men burn the boats– meaning we’re either going to take this land, or we’re going to die here.

I inadvertently did that when I got laid off. I chose not to go and get another corporate job. I said, this is what I really want to do.

I had been building a portfolio of work prior to this, I had done a proof of concept TV pilot that had played at Tribeca, and I had some success. But it’s also that question that was masking all of my insecurities and fears. And it was a way for me to put them on the table that I felt comfortable with, and that you were able to read through and go, this guy just needs someone to be honest with him.

The greatest gift was you saying, you don’t have to believe any of this stuff. Because that gave me security to come to it on my own terms in my own time. But I was terrified, because at some level realized that I had said, burn the boats! I was either going to make it or I wasn’t.

I had to face the fact that, up until that point in my life, I always had an excuse. I’ve got a full-time job, and I’ve got family needs, and I need to take care of those people. And I always had a reason that I hadn’t “made it” or gotten to the place where I wanted to be.

Without the job as an excuse, I realized I would have no excuses, I would either make it or I wouldn’t. That’s a terrifying prospect.

I didn’t quite realize all of this at the time, mind you!

When I was on this retreat, I knew there were things I was doing well, and I knew there were things I wasn’t doing as well. But I literally had only taken that one screenplay class.

That one screenwriting class when I was in grad school, that’s the only formal coursework I had ever done. Everything else was self-taught. And partly because, again, it was all my insecurity, I was like, if I have to take a class, that means I’m not good at it. I look back on it now. And I’m like, What the hell is my problem?

It’s all the insecurity that builds up in us. We don’t want to be bad at something before we can get good at it. It’s also that the stuff is very personal. And it should be. If it isn’t personal in some way, then we need to do some self-reflection as a writer and as an artist, and what the time in Costa Rica gave me boils down to two things.

One was a language for the things that I was doing well.

And the other was an understanding of the things that I wasn’t doing.

I remember having a conversation with one of the mentors about a scene I had written that was largely expository. And she said, Well, Christian, you just need to weaponize it. And I was like, Weaponize it? What’s that?

And then, all of a sudden, I realized, Oh, we need to feel the emotion underneath the information of this. This character has to use it as a weapon against another character. And suddenly, drama is there. Tension is there. Emotion is there.

As soon as I figured that out, I realized that once I have a word or language for the things I’m doing well and things I wasn’t, I could replicate things. I can say, Oh, I know what’s happening here. I’m not weaponizing the exposition, and therefore it feels flat, but if I let them turn to use that against another character, then the tension escalates.

The idea of having a language for this stuff was surprising to me. That was an aha! moment for me. Because I didn’t realize it could be, in some ways, as simple as that.

The other thing that I realized was giving feedback was something that I was terrified of. At the studio, we do it in a very specific way. And I didn’t want to be “wrong,” about how I was giving feedback.

But I really liked talking to writers about their work. One of the things that taught me the most is working with writers. You can’t go into a session with a writer and be like, Yeah, I couldn’t quite figure out what’s going on the page there. Sorry!

So it forced me to look at writing in a different way, working to go deeper and also really be thinking about what is this writer’s intention? What are they trying to communicate? What are the themes they are trying to explore? Not me, not what I think they should be doing. But what they are trying to accomplish.

And that gave me greater insight into my own work. What am I trying to explore here? How deliberate am I being with every word that’s on the page?

At that time, I wasn’t being deliberate with every word on the page, even though I thought I was. We think we know, but we don’t know what we don’t know!

That was the place where I started burning the boats and started really embracing the idea I think I can do this for real.

Jake: Well, I think it’s really interesting when you said, Well, I didn’t realize all that at the time.In a way, you’re kind of describing the rewrite process when you talk about that.

We have to be present in our scenes. But you can’t be present in your scene and carefully choosing every word at the same time! You can’t be present in your scene, and also thinking about, what am I building for the future? at the same time.

It is kind of a burn the boats situation when you show up at the page. You just have to do it.

And sometimes it’s not until you’ve completed a draft, that you can look back and go, Oh, that’s what I’m doing! Oh, that’s my intention!

We think we’re supposed to have it all worked out, and know what our intentions are, before we even write anything, but it’s impossible. You have to go through the writing to figure out what you’re actually saying.

Christian: Yeah, it’s always fun, starting a new project with the writer. They send their first 10 pages over and everybody knows how important those first 10 pages are; those first pages really are the most important in the script. And they’ve worked so hard, and they go, what did you think?

And I go I have to be honest with you, it doesn’t really matter.

And they look at me like, What do you mean, it doesn’t matter?

This is the way I work with writers. It’s not about what I like or dislike. It ‘s not about what things are good or bad or right or wrong. It’s about what do we gain or what do we lose with every choice we make?

In the last podcast, you’re talking about First Image in The Bear. And then we get into this conversation about first image, last image, how does that tell the story and all these things.

And the way we find these things is different for every writer. For me, I’ve never been a good outliner;. It feels like homework to me. My brain just resists it. I had to find my own process, I had to find my own way of doing things.

When I was writing City of Trees, I didn’t outline it, I wanted to remain really raw and close to my own experience.

The first draft of that was almost a dictation of things that had happened to me or my family and things I went through, I had to go through a process of making sure that it actually made good drama and fit it into the structure of a script, but going through that process, I always keep what I call a scratch document– that was not my idea, somebody else’s idea. But I have my screenplay document up and my scratch document up and whenever I delete a scene, I dump it into my scratch document.

I got to the end of that process of writing that script and went through 40 plus drafts, no joke. And the final screenplay was about over 107 pages, my scratch documents was 300 pages long.

Christian:I had essentially written the equivalent of four scripts, not even including all the drafts. And I just went, there’s got to be a better way. And I really started to think about process in that moment.

I spend a lot of time with writers talking about process, because I think that we have this tendency for this little voice to come into our head, the insecure voice, that when we get stuck, it says, See, I knew you weren’t good at this, you don’t even know why you’re wasting your time.

I realized that the way through that is process. It isn’t arguing with that voice. It’s asking what are the tools in my kit that are going to help me through it.

So I started this process. Now, when I start a new project, I have what I call a Story Notes Document. It’s just a Google Doc. And I just start dumping my thoughts into that document, because my brain is like this tangled mess and I constantly have thoughts intruding on other thoughts and stepping on each other, and I can’t start my way through it!

This is the way I usually write in the morning. Every morning I sit down when I’m starting a new project, and I just add to the document.

I essentially use what we teach in the Write Your Screenplay Class. Your characters: what are their wants? What are their deeper emotional needs for the obstacles in the way? What are their dominant traits? All that stuff that we talk about.

But I’ll be honest, when I started doing it, I didn’t realize that’s what I was doing, I was just following my intuition and being a curious writer. But I realized that’s what I was doing. I was essentially following what we teach in the Write Your Screenplay Class. And the way I do it, it’s not even prose. It’s like a letter to myself.

I was working on a script called In God We Rust. It’s a crime thriller. I’m obsessed with No Country for Old Men, the Coen brother’s movie. The ideas around mortality that are explored in that film and the arbitrary nature of life and death and things like that. Those really resonated with me. And the first lines of the story notes document for that particular script is “I feel like I’m circling something akin to No Country for Old Men, but I don’t want to straight up rip that off. And that allowed me the freedom to admit my greatest fear, which was I’m going to steal No Country for Old Men. And I put that on the table. Then I get to say, Okay, let’s make sure we don’t do that.

When I get into the screenplay document, my brain starts to formalize everything, and it starts to go, Okay, you’re the script now. And things get serious.

Even though my intellectual brain knows you’re going to need your lesson drafts and it’s fine, I still feel that pressure.

The Story Notes document allows me to be free and just come up with the craziest shit possible in a way that’s non-threatening, that I can make mistakes, I can fail on the page, and it doesn’t matter because I’m not in the script yet.

And don’t get me wrong. I’m going to fail a ton of times once I’m in the screenplay document too. But it’s something important to me, by allowing my brain to really be in this idea of divergent thinking and the opening of my process of exploring a script.

Eventually I’m going to get to convergent thinking, I’m going to start narrowing things down and making choices and saying, Oh, my character does this, my character lives here, my characters in this. But my brain is in such a hurry to get there, it can lead me to shortcut the process.

The quicker I get to the script, the more I’m shortcutting my ability to be curious and explore.

Jake: Yeah, I love what you’re saying about divergent vs. convergent thinking. I think of screenwriting, like filling an accordion. You’ve got to get it filled with air before you start squeezing stuff out. You need to fill it first.

I wanted to go back to something that you said earlier– obviously when I talk about our ProTrack program, it’s our program and I’m very proud of it. But one of the things I love most about ProTrack is that it’s about guiding the writer in those early drafts, past their own cynicism, fear, emotional blocks, challenges, structural challenges. Sometimes it’s pure craft. Sometimes you just don’t have the craft yet to actually know how to see it or know how to get it down on the page in a way that you can visualize it or hear it.

And this is why it’s so helpful, I think, just to have someone who’s so knowledgeable like Christian there at your side. Because, sometimes you don’t actually have the tools yet to diagnose where you need to be focused on. And if you don’t have the tool to know where you need to be focused, then you’re probably thinking about the 10,000 things you’re “supposed” to be doing. As opposed to the one thing that’s really going to move the needle for you.

And I love what you’re saying– to kind of tie that all together with your Costa Rica story, which I’m sorry I made you tell! I made Christian blush a little, telling that story. But I actually think we should go into any educational scenario with gentle skepticism. Because there are a lot of snake oil salespeople in this business.

And when Christian is talking about finding the language, that’s not the same language for everyone. That’s about developing your own personal language. And when Christian is talking about process, it’s not the same process for everyone, not everybody has the same process. It’s about developing your process.

And whether you’re working with us or someone else, one of the ways that you know that you’re getting good mentorship is that the mentor is asking you more questions, and that the mentor is sharing more of what their experience is, than they are telling you what to do.

In general, the more somebody tells you what to do, the more skeptical you should potentially be.

My attitude is, I’m a constant student. One of the pitfalls that a lot of teachers fall into is to get so identified with becoming the teacher that you forget that you’re allowed to learn! This happens after you sell your first script as well. You’re like, I’m a professional now. I have to be such an expert.

But that’s not true. We’re artists. And artists live in a place of beginner’s mind.

One of my heroes as an artist, (not as a human being, but as an artist) was Picasso. The reason I admire Picasso so much is that he was the best of the best at what he did, but every time he figured something out, he stopped doing it.

Every time he figured something out, he would reinvent himself. Well, I understand that, so I want to learn something new, I want to do something that I’ve never done before.

And I think that so nicely dovetails with what Christian was saying about confronting your fears, writing the thing that scares you. Pushing yourself.

The way I always look at education is this: I want to read every book. I want to study with anyone who has credentials. And when I say every book, I mean every book written by a real writer, not every book written by an academic who has never written a script. I want to take every class taught by a real writer– not by any writer, but by a writer that I admire. I want to attend. But just because they’re great at writing, I also have to know that that doesn’t mean that they’re great at teaching.

And just because their process gives great results for them doesn’t mean that their process is going to get great results for me. What I’ll usually do is simply go in with an open mind, Okay, I’m going to be gently skeptical, but I’m going to try everything you suggest.

Even when I read a book I mostly disagree with, a book like Save the Cat! for example. (I have a podcast about why I have problems with Save The Cat! If you’re curious). And there are brilliant things in Save the Cat! when it comes to the Producer Draft– he was a master of the Producer Draft of writing. He was terrible with character, which is why I struggle with him. But I wrote my Save the Cat! Movie. Okay let’s try it! Did it help me write a great screenplay? No. Did if help me learn a little something about the Producer Draft? Yes.

You can learn something from everybody. But what happens all too often is that we glom on to something like, this is the way, and I’m here to tell you: my way is not the way. Christians’ way is not the way. “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.”

Our way is not the way, and the job of your mentor is not to show you their way.

The job of a good mentor, I believe, is to help you figure out your way.

Christian: You know, if you want to learn something, teach it. It’s such a gift to work with these writers who are willing to share their work and their vulnerability with me. I learned so much from working with them. Because everybody’s got strengths. Good writers, good artists, good human beings are going to constantly challenge their base of knowledge, and go, how do I get better at this?

This is not a business where you can sit on your laurels. This is not a craft where you can just rely on the same thing every time. Every script that I write is different.

The most recent script I’ve been working on started like this: my producer and this director we work with, we’re all texting back and forth. And he was like, what about this idea of a hunter who’s out in the woods and finds a dead body. And I was, Oh, I can do stuff with that.

I took that, and luckily, in this case, my producer is very open to me running with things and saying now go write your version of it. And it turned into something that was very much weirder than probably he originally thought.

I had written a treatment. And I was like, man, this is flowing, this is going to be the easiest script I’ve ever written.

Yeah, you know exactly where this is going.

Then I hit a huge wall. And I’m still in the middle, I’ve probably come close to getting to the other side. That was two months ago. And I have a process for working through this stuff.

Every script is going to be different.

Every script is going to present its new set of challenges.

And if we’re not curious, if we’re not constantly open to learning things about the craft and about ourselves as writers, we’re going to hit a script one day that says, Nope, I’m not going to let you in. Unless we can be humble and curious we can’t find that access.

We all know that feeling of the muse coming down and touching us when we’re struggling… we’re taking the dog for a walk and we suddenly realize, That’s it! I just have to do that. And it seems so simple. Like, how come I didn’t think about this before?

I think as a professional writer, I don’t have the luxury of just sitting around waiting to take my dog for a walk and having the Muse come down. I have to cultivate that.

I’m not Buddhist, but I borrow from Buddhism. There’s different schools of thought of Buddhism, there’s the Sudden Enlightenment School, which is, you’re going to be walking down the street one day, and suddenly enlightenment is going to come down and it’s going to strike you, and you’re going to feel that bolt of lightning.

There’s another school of thought called Gradual Cultivation, which means you have to just constantly and consistently chip away at these ideas.

And I think it takes both to be a successful screenwriter.

You’ve got to have the discipline, and you’ve got to have the rigor and you’ve got to have just the patience, while still having a sense of urgency to go through that Gradual Cultivation and just chip away, chip away.

It’s really hard to do this stuff. But the more we do it, the more it becomes a routine, we do end up with a process. And we just have to be curious about it. And hopefully, there’s people along the way that can help draw that out of us.

I go back to the Latin root “educo” of the word educate, which means “to lead out.” It doesn’t say anything about indoctrination, it doesn’t say do it this way.

You’re leading that person out of the place that they are, to a place that is someplace new.

Jake: I have to talk about one more thing with you.

Christian you are starting up a brand-new Workshop at the Studio and I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that Workshop, and how it’s going to be constructed and what it’s going to do.

Christian: I’m really excited, because it’s a different way to work with writers. And one of the things that really has made me a better writer is understanding how to get feedback.

Normally, when we think about the Workshop environment, the first thing that comes to mind is, I get to have my pages workshopped, and people give me feedback. Don’t get me wrong, we’re going to do that, and that is a huge benefit.

But I think actually the underestimated benefit is learning how to read somebody else’s work. Learning how to read it in a way of supporting that writer, of being curious, of trying to understand what their goals are. Because that is also going to teach you how to read your own work.

It teaches you to take that judgmental voice– we can never get rid of it entirely– but part of the Workshop is going to teach you how to contextualize that voice, how to validate it in a way that allows you to listen to it more clearly. And to improve your own work.

Certainly, we’re also going to be talking about the words on the page. You’re going to get the opportunity to get feedback on your writing with a group of people who are intelligent, compassionate, caring, smart, and strong writers in their own right. But you’re also going to learn how to read stuff, and how to approach it with curiosity.

What better way to learn than to put your work out there and also help contribute to somebody else’s success?

Jake: The way these groups work is so wonderful. You do have to apply. It’s a very carefully cultivated group. We want to make sure that we’re putting the right people in the room.

There’s an interview process that you go through with our Admissions Director, James Kautz, where he’s going to talk to you about your writing, your goals, your experience, and we’re going to make sure that we get the right people in the room together.

What we’re really trying to do in those groups is get people who are going to be a sparky room, almost like if you were putting together a writer’s room, where you have different people with different voices and different talents and different levels of experience and different expertise. And you put them together so they can all grow together.

It’s an ongoing class, kind of like ProTrack, the goal is you can stay there for years, you can stay there through your whole career if you want to, with this intimate group. Everyone commits to stay for a minimum of a year, so that there’s continuity so that you know each other’s work.

You’re going to meet twice a month, and there are only eight people, so, everyone’s getting a chance to workshop pages every other session. And you’re kind of building these pieces together. It’s just a really extraordinary way of learning, kind of like ProTrack in a group.

If you want to find out more about that, you can go to www.writeyourscreenplay.com and set up an appointment with James to talk about it.

Christian, if there was one other thing that you would want writers to know, one other gift that you’d like to give them, that you wish you had known when you started your journey, what would it be?

Christian: One of the things that we always come back to is what one of my mentors told me. He said, Christian, the people who make it are not the people with the most talent. They’re the people who stay in the room. And that’s something I’ve taken with me to this day.

When I’m working with writers, I remind them that there are so many things we cannot control. We can’t control how other people like our work. We can’t control whether somebody’s going to give us money. We can’t control whether they’re going to get it made.

But we can control the words on the page. And if we come back to that page, day after day, week, after week, month, after month, year after year, good things can happen. Stay in the room.

Jake: Yes, I love that, stay in the room. Keep digging till you find your voice. Decide you’re not going to let go of your script until you make it good, rather than asking yourself if you are good enough. And I think you’ll be surprised by just how beautiful your journey can be.

Thank you, Christian, so much for being with us, and for all this wonderful advice.

If you want to study with Christian you can do so online from anywhere in the world, one on one in ProTrack or in a group in his new Workshop.

If you’re interested in our other screenwriting, TV writing, playwriting or comics writing programs you can attend any class online from anywhere in the world!

If you want, you can even join us for free every Thursday at Thursday Night Writes where Christian is sometimes a guest. Thank you all so much and we’ll see you soon.

*Edited for length and clarity.