There’s a scene in the very last episode of The Bear, Season 2 – the episode titled “The Bear” — where Carmy is stuck inside of the walk-in refrigerator at the restaurant. Outside the walk-in refrigerator, all of Carmy’s dreams are actually coming true. His restaurant is actually a success. His team has actually come together against tremendous odds. Everybody has actually stepped up and bought in and everything is actually working.

But inside of the fridge Carmy cannot see it. Carmy is only stuck with his self-doubt, with the mistakes that he’s made. He is stuck inside his own ideas, and his history, and his past, and his patterns, and his problems and his imagination of what must be happening outside where he cannot see.

It occurs to me that the refrigerator scene in the finale of The Bear, Season 2 is a metaphor for how we as writers feel all the time during our writing process.

It is so hard to actually evaluate our own work. It’s so hard to see if our writing is working, because in the process of building our dreams, we are going to make so many mistakes, we are going to fall short, we are going to grapple with our patterns, and our history, and our family history and our traumas. Because we’re going to grapple with all that, we are so often actually inside the refrigerator where we cannot see the beauty in front of us, where we cannot actually allow the good to be good.

So that’s what we’re going to be talking about in this episode. We’re going to be looking at the final season of The Bear. But what we’re really going to be exploring is the process of writing, the process of rewriting, the process of turning something that doesn’t work into something that does work.

And the most important part of that process is the process of dealing with our own self-doubt, our own self-criticism, our own self-blame, our own patterns, our own fears, our own spiraling, in order to actually get out of the refrigerator and be able to see the beauty of our own writing.

A warning, there are going to be some spoilers ahead. So if you haven’t watched The Bear, Season 2 yet, you might want to do so; however, even if you haven’t seen The Bear, a lot of the content of this podcast will still be very valuable for you.

So let’s talk briefly about how The Bear works as a series.

If you’ve listened to my episode on The Bear, Season 1, you already know some of this, but we’re just going to do a quick recap. In Season 1 of The Bear, we meet this team trying to do the impossible – they are trying to run a restaurant. And we are caught in the heat and the emotions of a kitchen where nothing is working, where everyone is at cross-purposes, where everyone is fighting, where, emotionally, people don’t know what they mean to each other yet.

We’re going to watch a world of deeply dysfunctional but also beautiful people learn what they mean to each other, learn to show up for each other, learn to love each other. And just when everything seems like it’s finally coming together, we’re going to watch “the bear” in Carmy come out.

In the first season of The Bear, Carmy is a world-class chef who has come home to Chicago after his brother Michael’s suicide to take over Michael’s crappy, dying restaurant. Carmy’s decision doesn’t make sense rationally. It only makes sense emotionally for him to do this. We don’t know a lot of why. We don’t know a lot of the past. We don’t know a lot of the history. But we know that this place and the people in this place are a mess, and that they are all under so much intense pressure at every moment of every day that they just can’t seem to get ahead. They can’t even seem to get caught up. They are constantly digging out of their own mistakes.

Over the course of the first season of The Bear, Carmy is going to instill new values into his team. And he’s not going to do it Ted Lasso style — he’s not going to do it with a smile and a grin and a wonderful ease. No, he’s going to do it in a beautiful and broken way. He’s going to do it by bringing all of his beauty and all of his dysfunction into the mix at the same time.

Over the course of the first season, a really powerful relationship is going to grow between Carmy and Sydney under the pressure cooker of this kitchen. And just when it seems like he’s actually succeeded at the end of the first season, everything is going to blow up. “The bear” inside of Carmy is going to come out. He is going to lose it on Sydney and he is going to destroy everything he built.

And on the other side of that, they’re going to find an unexpected new sense of hope. In fact, they’re going to find a little gift that they didn’t even realize existed, left by his brother Michael…

…a little spoiler ahead for the first season…

…in a bunch of canned tomatoes Michael has secretly hidden all the money that they need to actually turn the restaurant into something.

You can see how this fits with the theme of The Bear — what the show is actually about.

The Bear is really just Ted Lasso with edge.

It’s really just a show about what happens when somebody who cares comes into an environment where people have been trained not to care. How that transcends culture, how that transforms people, how that allows people to get beyond their own limitations and their past. And how it allows people to actually see the love that is right in front of them that they are so often missing.

That’s the structure of the first season of The Bear. It’s Ted Lasso, with a lot of edge.

So if you’ve just completed the first season of The Bear–one of the great first seasons of all time –and now you have to create a second season, there’s a good chance you’re going to freak out as a writer.

It’s terrifying, right? How do you ever live up to those heights? Especially because it seems like the writers of The Bear have broken their own series engine by the end of the first season.

At the beginning of the first season, none of these people know what they mean to each other. The love is not there. It takes getting all the way to the end of the season and building that love for the show to actually work. It takes getting to the end of the season and building that love for these people to actually understand what they mean to each other.

So how do the writers of The Bear re-create the feeling of Season 1 as they go to Season 2? How do they reset the series engine?

The pressure of Season 1 is all about the following elements: they don’t have enough money, they don’t have enough skill, they don’t have enough time — all the pressure. But at the end of Season 1 of The Bear, the writers have gifted them with everything they need. So how are they going to find the conflict in Season 2? How are they going to move these people who have already moved so far? And how are they going to do it in a way that feels the same, but also different?

This is where most screenwriters freak out. How do I ever do it again?

But like everything, the answers that you need are right in front of you. Like everything with writing — and I truly believe this — like everything with life, the answers are usually right in front of you — hiding in plain sight.

The problem is that we are often locked in our refrigerators, locked in the refrigerators of the past, replaying things the way that they’ve happened before, instead of imagining that maybe they could happen differently.

In television, we’re trying to figure out how it can be the same but different — every episode and every season. And that doesn’t grow from being super-creative. It actually grows from looking at what already exists, asking “what’s already working?” and then getting creative around that.

And you can ask this simple question — “What’s already working?” – when developing any series or any movie, no matter how flawed, or how problematic, or even how complete it already seems to be.

If you’ve just written a pilot and you’re trying to figure out what the engine is, you can ask this about your pilot. If you’ve written a feature and you’re trying to figure out what a sequel looks like, you can ask it about your feature. If you have written an act and you’re trying to figure out what the hell happens from here, you can ask it about your act. If you’ve written a beautiful scene that doesn’t yet feel like a movie, you can ask this about your scene. If somebody has asked you, or if you’ve asked yourself, “Does this actually have legs? Is it a movie? Is it enough?” you can ask, “What’s already working?”

The answers aren’t out there in the ether. The answers are not in your brilliant creative imagination. The answers are in what you’ve already written. And you can build everything you need just by looking at what kinds of things already happened in your screenplay that already work.

If you’re trying to build a second season of a successful series like The Bear, (or even to imagine one when writing a TV bible for an unproduced series) start by asking yourself what already works? What kinds of things happen in Season 1, and how can they happen again in Season 2?

If you look at The Bear, Season 1, what happens? A relationship is built between Carmy, a man who struggles with relationships, and a well-meaning person who makes herself vulnerable to him. In the first season, that’s Sydney. In the second season, that’s Claire.

In The Bear, Season 1, everything is focused around the kitchen. There’s never enough time and there’s never enough resources. In Season 2, it looks like we fixed that problem. So we need to find a way to reset it. The way to reset it is simple. It turns out, if you watch the pilot, that “everything” turns out to be “not enough.” They still don’t have enough money and, therefore, they have to make a deal whereby if they don’t open the restaurant fast enough — which is too fast — they’re going to lose not only the restaurant but also the building. They’re going to lose everything.

And you can see that’s just a resetting of the stakes.

Part of the stakes in Season 1 of The Bear is that the restaurant may fail and they might lose everything. In Season 2, they just find a way to reset it. They have to make a deal to get more money and now they have to do it faster than it can be done. And if they fail, they’re gonna lose even more everything. The stakes are reset: we’ve got the time pressure back.

Now, an interesting thing happens with the kitchen. In Season One, the kitchen is a pretty narrow definition, it is literally the kitchen of the restaurant. But in Season Two, they’re trying to transform the restaurant into something really big — a high-end restaurant as opposed to the low- end restaurant they’ve been up till now. And that means, if we’re just realistic about it as writers, there’s a huge build-out happening. So how do you focus Season 2 in the restaurant?

They make a really interesting choice. Season One is entirely contained. In Season Two, they open it up. They start to send the characters to other restaurants — places where they have to grow or fail to grow beyond what was possible in Season One.

Even though they’ve changed the location of The Bear, Season 2 from one crappy kitchen to many kitchens of all different types, they’re actually building the same engine.

The engine of The Bear centers around the pressure of the kitchen, and the way that pressure helps people learn what really matters to them: to earn and fail and learn and fail until they discover what it takes to actually be great – not from the outside but from the inside.

While we’re going to see this with a lot of the characters, we’re going to see this most clearly in Season 2 of The Bear with the character of Richie, who is going to go through a total A to Z change in this season.

Richie — who has been a fuck up his whole life, who has cut every corner his whole life, who has made impulsive decision after impulsive decision after impulsive decision his whole frickin’ life — is going to go on a journey that humbles him and changes him and allows him to find the will, the desire, the dream inside of himself that allows him to actually care. And actually realize that he matters. And actually find the love for himself that it takes to really do his job.

Richie’s going to go on a huge, profound journey in Season 2 of The Bear. But this is just a mirror for what happens to the entire team in Season 1. It’s the same engine. But there are other places where the engine changes in radical ways.

Season 1 is built around a relationship between Carmy and Sydney. But in Season 2, Sydney is going to be constantly left on her own.

This is one of the most interesting choices in The Bear, Season 2, because it shows how much flexibility you have in your engine. You don’t have to do things that aren’t going to work again.

The truth is, in Season 1 of The Bear, the journey of Carmy and Sydney together has gone as far as it can go. So instead of trying to squeeze more juice out of a fully squeezed lemon, they do a reversal of it.

Carmy is building a different relationship. This time his relationship is with Claire, which is pulling him away from Sydney and away from the restaurant.

But Carmy’s relationship with Claire is doing the same thing structurally in the second season as the relationship with Sidney did in the first season. It’s serving the same purpose in The Bear’s engine.

Carmy’s relationship with Claire, just like his relationship with Sydney in the first season of The Bear, is bringing out a part of Carmy that he until now has not dealt with — the part of him that wants love, the part of him that can be vulnerable, the part of him that can take risks, the part of him that wants that kind of beauty, too.

So you can see the Carmy-Sydney relationship gets replaced by the Carmy-Claire relationship, but it’s doing the same thing. And just like the Carmy-Sydney relationship in Season 1, Carmy’s relationship with Claire is going to culminate when “the bear” comes out of Carmy and blows it all up. Because that is how the engine of The Bear works.

Smack dab in the middle of Season 2 of The Bear, there’s a Christmas episode called “Seven Fishes.” It’s an hour-long episode in a show that is normally 30 minutes. And it’s like watching Long Day’s Journey into Night.

It is one of the darkest episodes we have seen on television in a long time — not just of The Bear but of any show. And it seems like once again, it’s breaking all the rules. Kind of like the Christmas episode of Ted Lasso, where you’re like, What the hell just happened? Well, it’s the same feeling here, what the hell just happened?

Carmy finally connected with Claire and then suddenly we’re in the past. Suddenly, we’re at a Christmas dinner in an episode that’s airing nowhere around Christmas. Suddenly, there are all these characters we’ve never even met before. Carmy’s mom, Donna, and all these larger-than-life characters that are not even normally part of the cast.

But even this Christmas episode is still doing the engine of the show, meaning everything still happens in the kitchen.

Everything is built around Donna trying to make Christmas dinner. And though there is no physical refrigerator that she’s stuck in, she is actually stuck in the refrigerator of her own beliefs. Because every single character in the show is trying to help her and love her and appreciate her. And as she gets drunker and drunker and more and more scared and more and more under pressure trying to make the meal work, she pushes everyone away harder and harder and harder.

Playing her own fictional story, Donna literally cannot see what’s right in front of her, she cannot see the love, she cannot see the beauty. She repeats the story of no one appreciates me, no one wants to help me, nobody cares about me — until “the bear” comes out in her and just blows up everything.

You can see the show is doing the same thing again and again and again in different ways. It is showing us “the bear” that lives in all of these characters that is just so hard to overcome. The way that the blinders of our past, the stories we’ve been telling ourselves about the past, our past failures, our past habits, our past relationships, our past history, get in the way and create a “refrigerator” in which we cannot see the beauty, even as it is happening all around us.

And we end up blowing it up.

The Bear is showing us the results of a world in which we cannot see the love around us. And we cannot see our love for each other. And we cannot see our love for ourselves. And it is also showing us the other side of that, when we do realize what we mean to each other.

That’s what the show is about. That’s how the engine works. And that’s why, even though it looks like the construction of The Bear, Season 2 is so different from Season 1, the feeling of Season 2 is exactly the same.

In Season 1 we have very little backstory, other than knowing that Carmy’s brother, Michael, killed himself. In Season 2, we’re going to go deeper and deeper and deeper, and we’re going to start to really understand the lives of these characters outside the restaurant — the pasts of these characters.

But the journey is always the same. The kinds of things that happen in The Bear happen around food and pressure and not seeing the love that is right in front of you.

I’d like to suggest to you that there’s a good chance in your own writing that you are stuck in a “refrigerator.”

I would like to suggest to you that nearly every screenwriter at some point has looked at something beautiful they’ve written and said, “You suck. You’re not good enough. I failed this project. I wasn’t up to snuff. I wasn’t able to pull my weight. I got distracted. I lost steam. I didn’t show up. I failed.”

Every one of us has worked really hard at something and then looked at it and called it a total failure, a total piece of shit. Every one of us has lost hope.

But what I’d like to suggest to you is that just like in Carmy’s restaurant, there are probably beautiful things happening in your script that you are not yet able to see.

Getting out of the “refrigerator” and seeing the beauty in your writing begins with understanding which phase of the writing process you are currently in.

In Season 1 of The Bear, the restaurant is the Original Beef of Chicagoland. And in an early draft of your script (in “Season 1” of your script to continue the metaphor), there’s a good chance that your draft looks a lot more like the mess of the Original Beef of Chicagoland than the future fine-dining establishment of The Bear.

There’s a good chance that the walls are falling down. There’s a good chance that the characters don’t yet know who they are to you or to each other. There’s a good chance that the product isn’t good enough yet. And there’s a good chance that you are going to look at what you’ve written and dismiss it as just a shitty restaurant that doesn’t have the potential to succeed.

There’s a good chance that you are bringing to that analysis not only a subjective judgment of oh, interesting to see what’s missing in what I’ve written, but also a whole history of pain and trauma and fear and family relationships and people who doubted you and doubts you’ve had about yourself. And the mistakes you’ve made and the ways you’ve let other people down, and the battle that we all fight around being an artist in a society that’s not made for artists, and the internal battle of believing in our choices and believing that we’re good enough to do it.

And just like Carmy does with the characters in The Bear, there’s often an instinct to think, my characters aren’t good enough.

But no. We, like Carmy, need to start addressing all of our characters as “Chef,” regardless of their current condition. We need to start noticing, “Well, there is something beautiful in them.” Even Richie can turn into a guy who cares.

And that is not about changing who your characters are– that is about looking more closely and asking: who are they already? What is already showing up clearly about them?

In other words, it’s the same question: “What’s already working?” Then you get to ask yourself a simple follow-up: “Where could they go from here?”

I don’t care if 200 things don’t work. It’s always about finding that one thing that does work.

This is the kind of thing that’s going to happen in the show. This is the kind of thing that’s going to happen in this movie. So how do I do more of that? How do I push that further? How do I build on that?”

That might be about finding the one line that your character says that feels “so them” and asking yourself, “OK, if this is true, what else is true? If this is true, what might the next line sound like? If this is true, if this is the wave, where’s the undertow? What’s the part of the character they’re not showing to the world? And how can I put them in a situation of pressure when that will come out?”

It’s our job to transform the Original Beef of Chicagoland into a living breathing entity that is filled with relationships.

This is one of the keys to being a screenwriter – it’s realizing, it is never your plot. It doesn’t matter if you’re building the Original Beef of Chicagoland or the high-end restaurant The Bear. It doesn’t matter which one you’re building. It’s the relationships between the characters that make the movie or make the show. It is not the crap that happens to happen.

It’s your job as a screenwriter to fall in love with your characters. Discover the beauty in them and allow them to put pressure on each other as they get what they want — or as they try to get what they want — so that they can go on a journey.

It is your job as a screenwriter to let yourself out of the refrigerator so that you can start seeing the beauty around you. Because it’s only by seeing the beauty that you can actually build.

The Four Phases of Writing

If you’ve taken my Write Your Screenplay class, you know the four phases of writing, and how to access them in your own process as a writer.

In the Me draft, we have to find the beauty of characters. To do so, we have to get past our inner censor and our old habits. We have to imagine that it could actually be different, we have to allow our characters to emerge, we have to trust them, we have to send them on journeys, we have to allow them to fail, we have to let go of our tight hold of the way we think things have to be.

And eventually, like Carmy unwittingly ends up doing in Season 2 of The Bear, we have to build relationships that are so powerful that they will actually carry the show or the movie without us– just like Carmy’s team carries the restaurant.

We have to realize that actually, we are not the driving force in our shows or movies or novels or plays, that actually the characters are.

We have to realize that, sometimes, our job is to get out of the way and notice what’s beautiful.

Sometimes our job is to let the characters start writing themselves, like they do in the final episode of The Bear, Season 2.

But our desire to control them, our fears of failure, our need to stick to the plot, our need for it to go a certain way, our need to follow the outline, our need for it to be commercial, our need for it to sell — this is actually what gets in the way.

Our rigid belief that “I can’t have this and also that” is what gets in our way of realizing our full potential as screenwriters.

Carmy’s belief that he can’t be a successful restaurateur and also have a beautiful relationship in his life — when actually he’s been doing it the whole season– is what gets in the way of his success, just like so many writers who have similar limiting beliefs, like “I can’t be a successful screenwriter and also have beautiful relationships in my life,” or “I can’t be a screenwriter and also be a mom,” or “I can’t be a screenwriter because I’m too old, or too young, or too late, or too early, or too smart, or too dumb, or too busy or too scared…”

Our job is to see the beauty. Our job is to get out of the refrigerator. Our job is to recognize that we are not the same person today that we were when we sat down to write the script.

In The Me draft, we have to allow those characters to come to life. We have to take risks, we have to break things, we have to write the hour-long episode that doesn’t make sense. We have to follow our instincts and our intuition, the things that we didn’t plan.

Once you have discovered the beauty in your writing, you can use the following phases of writing to shape it.

In the Audience draft, the second phase of writing, we need to bring order to the chaos so that other people can get it, so that it can work, so the pieces can work together like the characters do in Season 1. We have to build the Original Beef of Chicagoland.

But almost all of us will realize at a certain point in the development of our screenplays, “You know what? The Original Beef of Chicagoland isn’t actually what I meant to build. I actually wanted to build The Bear. I actually wanted to build something that is bigger than the dream I had when I first sat down to write.”

That’s a natural part of the writing process. And as a phase of writing, it’s what I call the Producer draft.

In other words, at some point you realize this thing is leaning towards something bigger than you imagined it could be — something scarier, something harder. But also something more compelling and more interesting. You ultimately realize it’s not enough for it just to be hot and make sense. It has to live inside of something undeniably cool that grows out of the process of writing it. That makes people go, Yes, I get this! That gives it a shot in a very competitive industry.

The piece itself is going to morph and change as you morph and change, and eventually, you’re going to have to love yourself enough to take the next leap of faith and transform it: not into what you planned it to be, but into what it wants to be.

Eventually in order to surprise and delight ourselves and surprise and delight our audiences, our shows and our movies are going to have to go beyond our original conceptions. Because there’s a good chance that our original conceptions of our screenplays are limited by the confines of our own refrigerators–by our past, by our beliefs in ourselves, by the stories we’ve seen before.

Every place your script wants to go is already in your script. But you’ve got to step out of the “refrigerator” to see it.

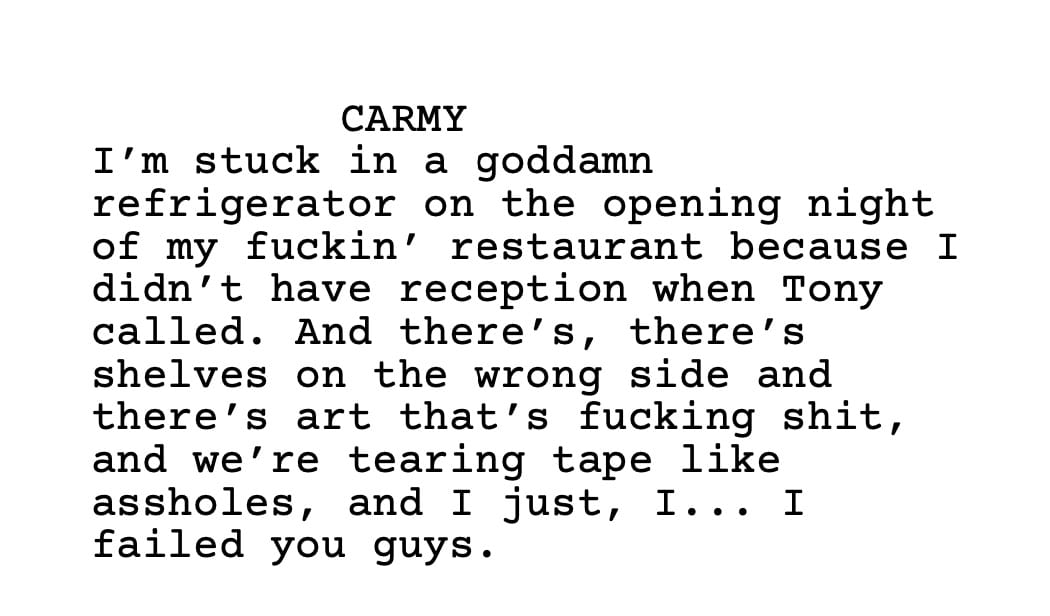

So I’m going to take a moment now to walk you through this incredible scene from the Season Finale of The Bear, Season 2. The scene in the refrigerator we’ve been talking about.

Prior to this moment with Carmy in the refrigerator, we’ve actually just seen the inspiring crescendo of everything that he’s been trying to build. Richie has served Uncle Jimmy a chocolate-covered banana, and that chocolate-covered banana is a symbol of what it actually means to run a restaurant — and quite frankly what it actually means to write a screenplay. Which is to share with the audience something beautiful in you, and something beautiful for them, something that transforms them, that shapes them, that changes them forever.

The serving of that banana is the end of a beautiful journey for Richie. It’s the end of a beautiful journey for Uncle Jimmy. And it’s the culmination of opening night. The restaurant is actually doing what it’s meant to do. It’s just not doing it the way Carmy imagined.

And we cut to Carmy in the fridge, where he is speaking his feelings at the moment to Tina.

And this is exactly how we feel as screenwriters in early drafts or middle drafts or even when we’re so close to the final draft. We actually have this thing that is one step away from being beautiful and marketable and everything we want it to be. But instead we’re seeing the “no reception” and the “broken handle” and the “bad art” and the “cabinet” that’s on the wrong side.

We’re looking for the problems rather than looking for the beauty. And we’re feeling like failures because we can only see the problems.

And this is why it’s so important for you as a screenwriter to change your perspective. Do not start by looking for what doesn’t work. Don’t do it in your script. Don’t do it in your life. Don’t start by looking for what sucks about the characters. Don’t start by looking for what you’re discontent with. Start by looking for what’s beautiful. Because those are the things you can build on.

And while Carmy is melting down inside the refrigerator, we cut outside to Claire and Fak and we’re seeing the end result that is so in reach. Yes, things need to be cleaned up, but the characters are actually achieving what they’re meant to do. And they are basking in the beauty of it. But Carmy’s not seeing it.

Probably if you’re a screenwriter, you have that cheerleader, you have someone like Tina that’s going, “That’s so silly” as you doubt yourself. But just like Fak describes him, Carmy feels like he is in this fridge alone. He doesn’t realize that the characters are there to support him. He thinks he has to do it all by himself. He doesn’t. But he thinks he has to do it all by himself. He doesn’t realize the characters can actually carry him.

And Sydney, of course, is having her meltdown as well. She has just achieved the biggest accomplishment of her life. But she is looking at the printer that pops out the orders and she is flashing back to the previous season when everything fell apart around that. And so instead of being able to fully experience the beauty of what happens, she actually ends up running outside and throwing up. It’s that hard for her to just see what she’s actually accomplished.

Meanwhile, Carmy is asking the question that literally every screenwriter has ever asked. “Maybe I’m just not built for this.” He’s asking, “Am I good enough?” as opposed to “What’s already beautiful?” He’s asking, “Can I do this?” rather than “What can I build on?”

So Sydney ends up sending Tina away. And Claire ends up pushing her way back into the kitchen because she’s worried about Carmy. And Sydney’s throwing up. We’re at the pinnacle of success. It’s not perfect yet, but we’re at the pinnacle of success. And neither of these characters can see it.

So here’s what’s actually going on: The food was so awesome. People are loving it.

And here’s what’s going on in Carmy’s head:

What Carmy is doing here as he monologues is making the choice that most writers end up making. He ends up deciding that what he was trying to have, what he really wanted, is too big. He has reached for something that was beyond his original conception. And just like most people, like any artist, he doesn’t know how to do it yet. And so he ends up pushing the big dream away to stick with the old patterns that he knows haven’t worked for him.

We’ve been watching his old patterns not work for two seasons. But they seem so much less scary than his new patterns.

This is exactly what we do as writers, right? We cut ourselves off from our real dreams.

“I really want to write this. But is it commercial? I really want to write this. But can I sell it? I really want to write this, but am I good enough? I really want it to be both this and that. But can I do it right? Maybe I’m not made for this, maybe I should just do the simple thing even though it’s not that compelling. Even though it hasn’t worked in the past, maybe I should just stay as I am rather than taking that step into the unknown.”

This might be the saddest sequence in the whole series. “I don’t need to provide amusement and enjoyment. I don’t need to receive amusement and enjoyment.”

What Carmy has just done is transformed his art just back into another shitty job.

And this is also something that screenwriters do — we forget that this is art, we forget that this is fun, we forget that this is supposed to fill our lives, not consume it. We forget that our outside relationships can actually fuel our inside relationships, and the other way around.

We forget that this is play and we are privileged to be in the position where we can play.

All of us have said that. And some of us have actually chosen that. Not realizing the diminishment that comes with that.

Because just like Carmy is in love and has built a restaurant, you are an artist. And you actually cannot step away from that and still be you.

And learning how to not do that, learning how to step into it, even when you are failing, even when you are not yet good enough, even when you are doubting, even when it hurts so bad, that is actually the process of becoming an artist.

And of course Carmy doesn’t realize this whole time he’s been speaking to his girlfriend. He doesn’t realize she’s outside, he can’t see her there caring for him. In fact, he doesn’t even know she left him a message on his voicemail where she’s actually told him how much she loves him and how much he means to her. He doesn’t know, he cannot see it.

And I want to suggest to you that when you have these internal conversations in your head, you are actually shutting down the characters that are calling to you in your script, begging you to let them show up and support you.

When you have those conversations with yourself, when you say none of this is worth it, it hurts too much, it’s too hard, I’m not good enough… When you allow those doubts to take you over, when you allow the refrigerator door to close and not recognize who is on the other side.

What you inadvertently do is take these beautiful characters that live inside of you, that are trying to come out and you shut the door on them too.

So I’d like to suggest to you to open the door.

Because all you have to do is listen and your characters will take you somewhere beautiful.

Let’s just watch where we go from here.

The moment he realizes he’s actually speaking to Claire, everything changes for Carmy. The moment he becomes aware of the character on the other side of the door, everything changes.

And this is a drama, so it’s too late maybe for Carmy but it’s not too late for you.

The beautiful thing about being a screenwriter is that you can actually choose to open the door at any time. You just have to ask yourself, Am I willing to love myself enough? Am I willing to love my characters enough? Am I willing to allow myself to love this enough to move through the doubt and move through the pain and discover something new?

Because if you don’t do that, what lives on the other side is something like the scene we’re about to watch now. After Claire has left and said goodbye to Richie, and Richie comes and knocks on the door and tries to break through to Carmy.

If you look at what’s happening in this scene, the two of them are actually standing on opposite sides of the door. The framing of the shot is so incredible. Neither of them can see each other.

And here it is. Richie has just called Carmy on his stuff. Carmy is not being Carmy in this scene: Carmy is being “Donna.”

Carmy is replaying his past. He is staring at a refrigerator door instead of what is in front of him. And there’s a character going, “Don’t you see it?” And he just keeps doubling down, not because he’s bad, not because he’s wrong, but because he cannot see the love in front of him.

In fact, the scene is going to culminate with Richie saying, “I love you, I love you, I love you” and still not being heard.

So this is your job as a writer, and it’s actually this simple. Your job as a writer is to let something beautiful be beautiful.

So this is my question for you — and I want you just to take a moment to think about it.

What will it take for you to open that refrigerator door? What will it take for you to see what’s already beautiful in your writing? What will it take for you to trust the characters that you’ve already created and allow them to carry you? What will it take for you to realize that you’re actually in this together?

What will you need to learn in order to build a new story, not the one that you’ve built in the past but the one that you desperately need to tell?

What will it take for you to let that beauty into your life?

I hope that you enjoyed this podcast. If you want to learn more about how to unearth that voice, how to find the beauty in your script and how to build it, then come check out my classes in screenwriting and TV writing, my Master Class or our ProTrack mentorship program at WriteYourScreenplay.com.

You can do it all live, online, from the comfort of your own home. So come check it out.