The Banshees Of Inisherin: Allegory, Stakes and Structure

This week we’re going to be looking at The Banshees of Inisherin, by Martin McDonagh.

It was fascinating to see The Banshees of Inisherin up against Everything Everywhere All at Once at the Golden Globes, because Everything Everywhere All at Once was such an extraordinarily complicated screenplay, and The Banshees of Inisherin is such a simple one. It was very interesting to see those two scripts in head-to-head competition, because they represent the far extremes of what a great screenplay can be. The truth is, these are both highly effective screenplays.

Today, we’re going to talk about some of the more complicated elements underneath this apparently simple screenplay. We’re going to talk about the piece as a political allegory for the Irish Civil War and the troubles in Ireland that took place in the many years after it, and how Martin McDonagh’s incredible screenwriting makes this allegory work so well.

But first, I want to talk about one of the biggest accomplishments of the film: The Banshees of Inisherin creates stakes out of a situation that almost anyone would consider extremely low stakes.

Now, there are going to be some spoilers ahead. So if you have not yet watched The Banshees of Inisherin– what are you doing? Run out and watch it, and then come back here.

How does The Banshees of Inisherin build high stakes out of a low stakes situation?

The Banshees of Inisherin takes place on a mythical island during the Irish civil war, but the Irish Civil War is barely seen. It’s basically just some distant explosions and a couple of references. The characters live in a perfect, idyllic community– or at least, what seems like it. In the first image of the piece, we see this perfect rainbow over this beautiful town. And it’s very “green screened,” but it works that it looks fake. Because it’s so perfect, so happy– it almost feels like we’re going to start a musical or something.

We’re watching this nice guy named Pádraic Súilleabháin. He loves his life, he loves his sister, he loves his town and he loves his best friend, Colm Doherty. He goes looking for Colm so they can have a drink.

This is the normal world of The Banshees of Inisherin. It’s happiness turned up almost to a mythical level; it’s the kind of idyllic dream that we have of home. It’s the way this relatively simple man sees his home: as the loveliest place on earth. Pádraic knocks on his friend Colm’s door– the guy he has a pint with every single day at the pub– to pick him up. And Colm does not respond.

Structurally, what happens for the whole first half of The Banshees of Inisherin is simply Pádraic trying to understand why Colm doesn’t want to be his friend anymore.

In fact, it’s not until page 31 of the script, the end of Act One, that any threat of what’s going to happen in the movie actually occurs! It’s not until page 55 (of a 94-page script) that the first truly horrible thing happens.

That is incredible! It means that Martin McDonagh has basically created unflinching drama for more than half the script without actually allowing a single act of violence to happen.

He has wrestled one simple idea– “maybe he doesn’t want to be your friend anymore”– into nearly an hour of compelling screen time with tremendous stakes.

Why is your screenplay low stakes?

I’m going to be talking about how to build stakes in your screenwriting, and how to use The Banshees of Inisherin to understand stakes and how they’re built. Because building stakes is one of the most common notes that you will receive as a screenwriter.

So how do you write a script with high stakes?

You’re going to get this note all the time: “the stakes are low,” “it kind of felt low stakes,” “I wasn’t connected,” “I don’t know,” “I didn’t care.” And you’re sitting back, thinking, “I don’t understand. I blew up a school, I killed the baby, I set a dog on fire. Why is my screenplay low stakes?”

And then you see a movie like The Banshees of Inisherin, and for 55 pages, nothing happens. And yet we feel a tremendous sense of stakes.

So let’s talk about stakes and how you build them.

Almost always, when somebody says “the stakes are low” in your screenplay, it’s not because you haven’t killed somebody.

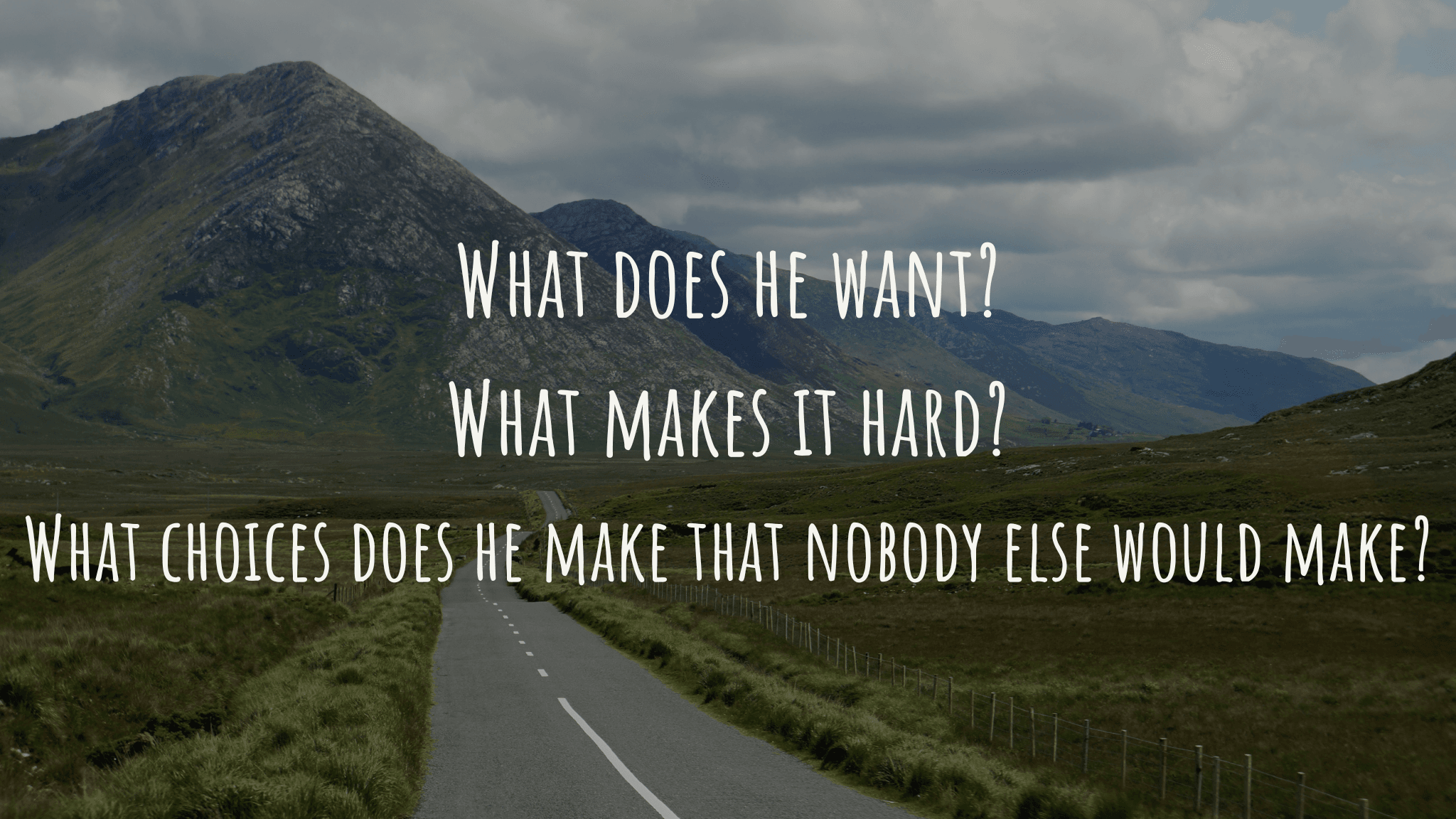

When somebody says the stakes are low in your screenplay, it almost always means either we don’t know what the character really wants, or we know what they want, but they’re not going for it with everything in they’ve got .

We’re not clear on how the character goes for what they want in a way that’s different from the way other people would. Another possibility is that we’re not sure what the obstacle is.

Almost always, when you get the “low stakes” note, it’s not about the plot. It’s about, “I don’t understand what the character wants, and what’s in their way.” Because stakes are, in a nutshell, just: What do they want, and what makes it hard?

Now, there’s another element of stakes: threat. Knowing what happens if the character fails.

Part of the reason Martin McDonagh is able to build high stakes in The Banshees of Inisherin, without even having the threat stated until 31 pages into the screenplay, is that his name is Martin McDonagh.

You have seen his movies– or at least you’ve heard about them. You know In Bruges. If you’re a fan of theater, you know that Martin McDonagh is famous for creating the bloodiest plays ever staged.

So part of the threat is that you know it’s a screenplay by Martin McDonagh. You know it’s going to get ugly, and you’re waiting to see how it gets ugly.

Just in case you don’t know who Martin McDonagh is, the movie is also called The Banshees of Inisherin. A banshee is a screaming harbinger of death. So you know something terrible is going to happen.

Even if you don’t know Marty, you know something terrible is going to happen just from the title. This shows you some of the power of a title.

Even if you don’t know what a banshee is, or who Martin McDonagh is, the first image of The Banshees of Inisherin tells you that something’s terrible is going to happen.

It doesn’t tell you something terrible’s going to happen by being a terrifying image, it tells you by being such an over-the-top positive image that there’s something impossible about it.

It’s one of those rare times when having bad special effects actually makes the scene even more effective. We know we’re not watching a Disney movie. We know that this is going to get ugly. So, we can feel the pressure inside that first image.

We have all those elements going for us, suggesting a threat in subtle ways.

And yet, we also have to recognize a lot of people don’t know what banshees are. A lot of people don’t know who Martin McDonagh is. A lot of people aren’t going to realize that we’re not in the beginning of a musical.

So yes, Martin McDonagh is building threat, but he’s building it in a way that only the most sensitive of viewers are going to actually get.

So why does The Banshees of Inisherin work for everybody?

As we can see from The Banshees of Inisherin, threat is a valuable element of stakes in a screenplay, but it’s not a necessary one. What is necessary is investment. That’s how the script builds stakes without an obvious threat.

At the start of the movie, we meet Pádraic. He’s so easy to get invested in because he loves his town and he loves his life, and we know what he wants. It’s actually the simplest want ever.

He wants to go get a drink with his good friend. He wants to say hi to the policeman who never says hi back. He wants to go to the pub and shoot the shit with what he would call some “regular talk”.

This is what the guy wants, we understand him, and we can get invested. He’s shown up to pick up Colm, and then the most unexpected thing happens.

He knocks on Colm’s window, and Colm just sits there smoking. He doesn’t respond at all. Neither we nor Pádraic know what to do with that, but we can feel his shock.

He goes home to his sister, and his sister says, “Are you rowing?” (Are you fighting?)

He responds, “I didn’t think we were rowing.”

And his sister teases him, “Maybe he just doesn’t like you anymore.” She’s just teasing, of course. It’s impossible. These guys love each other.

He goes to the bar, and they ask him the same question. “Was he sleeping? Are you rowing?”

Pádraic realizes, “Maybe we’re in a fight. Maybe I should go see him again.”

And the bartender says, “Yeah, I think that’s probably best.”

Think about The Banshees of Inisherin from a traditional, structural perspective. You have a character who wants something: to get a beer with his friend. That doesn’t seem high stakes. The stakes come from Pádraic’s actions in relation to the obstacle.

If Pádraic shows up, knocks on the door, Colm ignores him and Pádraic says “screw it” and goes and gets a drink on his own and never thinks about it again, then nothing happened. That’s not a movie.

But Pádraic’s actions build stakes. Pádraic’s navigating different obstacles. First, the extreme obstacle, the inciting incident: his friend not even responding to him. Then, the obstacle of his sister not getting that this could be real. After that, he’s dealing with the bartender asking him that same question, not processing the problem either.

No one’s seeing there could even be a problem here, but we’re seeing him want to get his answer: He needs to know why his friend is mad. We get sucked into the stakes of the same mystery he does. We care because he cares, because we feel him taking action.

So he goes running back to Colm’s house. He opens the door and goes inside, but his friend’s not there. He looks out and sees his friend heading away. Pádraic doesn’t know what to make of that.

Martin McDonagh just played the same game again; he just went back over the same obstacle, but outdid himself.

Pádraic goes back to the bar, orders a pint, tries to sit down next to Colm. And Colm asks him to move. Again, Pádraic wants to know what’s going on with his friend, so he says, “no, this is the beer I ordered.”

The bartender backs him, so Colm responds, “Okay, I’ll go outside.”

Now, you can see that this is exactly the same beat as what happened in the previous scene. But it outdoes the previous interaction with Colm.

Interaction number one: Pádraic goes to his house, the guy doesn’t respond at all.

Interaction number two: Pádraic goes to his house again, and Colm seems to have left just to be away from him.

Interaction number three: Colm chooses to go sit outside rather than sitting next to him at the bar.

How understanding the “game of the scene” lets us build stakes in screenwriting.

In comedy, we would call this the game of the scene. In comedy, you just keep playing the game again and again, and it gets funnier, and the stakes start to feel higher. We often forget that there’s a game of the scene in drama too, though, and that’s what we’re seeing here.

Our character takes a new action: he goes outside, and refuses to leave until Colm tells him why he’s angry. He needs to know what he did. Did he say something when he was drunk? Did he do something that upset Colm?

And Colm responds, “No, you didn’t do anything. I just don’t like you anymore.”

And with that bizarre little interaction, our main character is devastated. He’ll spend the rest of the movie just trying to make his friend like him again. Meanwhile, his friend will take and more drastic actions to end the friendship, until after page 55 it escalates into a full out civil war.

This is a very simple concept that I want you to keep in your head.

In the screenplay of The Banshees of Inisherin, Martin McDonagh structurally builds 55 pages of stakes entirely out of a character who wants something really bad, and who’s willing to take actions that most of us are not willing to take to get it.

Most of us, by the third time our friend tells us “dude, I just don’t like you anymore,” will simply give up and hang out with other people. But this character just needs to be liked. He needs to know he’s not dull. He needs to know he’s not the lowest in the pecking order.

And Martin McDonagh, being such a great screenwriter, keeps on picking on that need.

The guy that Pádraic thinks is lowest in the pecking order, the dumbest guy in the town, ends up knowing a word Pádraic doesn’t know: touché. Martin McDonagh’s knocking down Pádraic’s status through this simple interaction. And we, the audience, are having this incredibly personal journey watching a character trying to raise his status back up among his friends.

It’s not until page 31 of The Banshees of Inisherin, the end of Act 1, that we finally get the threat: “if you talk to me again,” Colm says, “I’m going to cut off one of my own fingers. And if you keep doing it, I’m going to keep on cutting off fingers.”

We start to realize, “holy crap, we know what’s going to happen in this movie. Colm is going to cut off a finger. Maybe all of ‘em.”

So we have 30 pages of just watching the characters escalate the issue. Colm escalates what he’s willing to do to keep from having to talk to this guy. Pádraic escalates the choices that he makes to try to break through to his friend. For 30 pages, we play the game of the scene, until finally Colm does something really crazy—he says that if Pádraic talks to him again, he’s going to cut off his own fingers.

If you know Martin McDonagh, you know he’s definitely going to do it. But even if you don’t, you both want him to do it and want him not to.

So you’re watching and you are predicting the future. You know that if the character doesn’t cut off his fingers, you’re going to be disappointed. You were promised cut off fingers, and if anything less happens it’s going to feel like the air going out of a balloon.

But it can’t happen exactly the way you expect it to, because if you just keep watching digits get cut off one by one, the movie is going to get really predictable and boring. When you’re playing the game of the scene, you have to keep outdoing yourself. You can’t do the same beat twice without escalating anything.

At the same time as you’re predicting those cut off fingers and knowing it has to happen, there’s another part of you that’s thinking, “I don’t want to see this guy get his fingers cut off. I don’t want to watch that.” You’re thinking, “Please, Pádraic, don’t talk to him.”

Structurally, the stakes in The Banshees of Inisherin are built in the same way as the stakes in a slasher or a serial killer movie. You know what’s coming and you know it’s going to be nasty, and you’re thinking, “don’t go up the stairs, don’t go up the stairs.” The same thing is happening here. “Don’t make him cut off his fingers. Don’t go talk to him.”

The stakes are growing and your tension is growing, because you know it’s going to happen and you’re just asking when and how.

And for the next 24 pages, Martin McDonagh is building the psychological process, the structural journey, the series of choices, the series of obstacles that lead our main character Pádraic to actually talk to Colm again.

It’s not until around page 55, almost an hour into The Banshees of Inisherin script, more than halfway through, the point we would call the “Midpoint” in a traditional 3 Act structure, (or the moment that we would call the “Sea Change” in the 7 Act structure we teach at the Studio) Pádraic pushes it too far and talks to Colm.

Slightly before we get to page 55, Pádraic gets drunk. He’s in the bar, he’s drunk… and we know he’s going to talk to Colm. And he does talk to Colm. Not only does he talk to Colm, he escalates things by attacking Colm.

It’s a bait-and-switch: we know what’s going to happen, but it can’t happen the way we expect.

So when Pádraic’s sister shows up and says “look, Colm, I’m going to talk to him. I’m going to make sure he doesn’t talk to you”, Colm has the most ironic reaction possible:

He says, “it’s kind of a shame, it’s the most interesting he’s ever been. I actually like him again.”

We think for just a moment, “maybe this isn’t going to play out the way we thought it was.” But we hear that teapot whistling in the background. We know what’s going to happen. But it didn’t happen the way we expected.

In fact, it’s when Pádraic shows up yet again and tries to apologize for attacking Colm at the pub. When Pádraic is sober, back to his normal self… that’s when it finally happens. Colm finally does it.

But even that can’t happen the way we think it will.

Anyone who knows Martin McDonagh is thinking they’re going to watch Colm cut off his finger in a grotesque and bloody scene. Instead, while Pádraic is talking to his sister, we hear a thunk in the background. Patrick goes running and sees Colm heading down the path. And then he sees the blood stain on his door, and the finger on the ground. And we have this horrible and funny scene with his sister, where he has to explain the finger on the ground.

And there, at the sea change, we’re propelled structurally into the second half of the screenplay, and a new version of the game of the scene that will escalate the stakes of The Banshees of Inisherin even further

In Pádraic’s position, any of us who’d gotten past “I don’t like you anymore,” would have given up when Colm cut off the finger. But Pádraic is going to keep playing the same game. He decides to bring the finger back to Colm.

This is where the stakes come from: The stakes come from a character who refuses to let go of what he wants, even in the face of obstacles that would have anyone else saying, “I’m out.”

Which leads to a fascinating thing: as Pádraic continues to try to break through to his friend, we start to realize that there’s a love between these two.

There’s a really beautiful interaction where they talk about Colm’s song: Colm has told Pádraic that now that he’s freed himself of Pádraic’s inane conversation, he is going to leave a legacy of music. He’s been working on a song called The Banshees of Inisherin, and he’s finished it. The two men have this beautiful moment where they talk about the song, and you can see the love that was once there.

We know what’s coming, but it’s not coming at us directly. It’s not coming at us the way that we expect it to. Right after that tender moment between the two of them, where they’re almost friends again, Colm finds out that Pádraic lied to chase his new musician friend off the island. So, he amplifies the stakes once again: he cuts off the other four fingers and throws them at Pádraic’s door.

Meanwhile, our main character is changing.

We met a guy at the beginning who was so nice, but no one appreciated his niceness because they thought he was dull. And over the course of the movie, he’s started to become meaner, because he thinks he’s got to be tough, to be less nice, in order to be loved by these people. Pádraic’s changing.

Colm’s changing, too. Colm starts out being totally cruel, but we’re seeing all the little chinks in his armor and wondering, “can these guys actually become friends again?” We know what we’re in for, but these little opportunities make us wonder if there could be another way.

These are the three questions Martin McDonagh uses to build high stakes in the structure of the screenplay of The Banshees of Inisherin.

What does he want?

What makes it hard?

What choices does he make that nobody else would make?

Those choices change him and change the people around him. Those choices he makes to get what he wants take him, Colm and his whole community on a journey to the terrible place we fear– even beyond it. But we don’t get there exactly the way we expect to.

This is where stakes come from. You can use threat, you can imply threat, and sometimes you can even get away without threat, as long as the want, the obstacle, and the choices are 100% clear.

So, at this point in the movie, we were expecting one finger at a time and got four. We know it just has to keep escalating, and it’s Martin McDonagh, so we know that whatever’s coming won’t be pretty.

But what we don’t see coming is another relationship that’s been built that matters to the main character.

The most important relationship in The Banshees of Inisherin has been built so subtly and hidden under so much humor that we haven’t even realized it. But Pádraic has four major relationships in his life, and this screenplay has already taken three of them.

There’s his sister, who’s left him forever because she’s tired of this crap. She has an opportunity on the mainland that will actually let her live a decent life, and her mythical island of tranquility and peace has turned to hell.

There’s Colm, his old friend who’s not his friend anymore.

There’s Dominic, the guy he looks down on, who’s basically his version of what he is to everybody else. He’s a nice guy, but he’s a little bit dull. But you talk to him, because you want to be nice, even though he’s a little bit of a pain in the butt. That’s who Pádraic is to the rest of the town, and that’s who Dominic is to Pádraic. But even Dominic doesn’t want to deal with him anymore, because he’s not the person he was at the beginning of the movie.

The only other relationship in Pádraic’s life is Jenny the donkey.

And it’s all handled so beautifully: all with comedy, using the same concept of want and obstacles.

Patrick wants the donkey to hang out in the house, because he’s sad and because he loves the donkey, because the donkey makes him feel better. Meanwhile, his sister wants the donkey out of the house because she is a normal, intelligent human being who doesn’t want a donkey in her house.

And so, there’s a running gag through the movie so far of Pádraic letting the donkey into the house. It’s all played for comedy, so you’re not even noticing that a relationship is being built.

But Martin McDonagh is building that relationship for a reason. He needs the relationship to matter to Pádraic so he can take The Banshees of Inisherin to a place you didn’t see coming.

There’s also a little running gag here that’s vital to the structure of the screenplay. It’s so subtle, but you’re always seeing Jenny trying to eat off the table. Jenny the donkey is always trying to eat something.

Well, Jenny the donkey ends up choking to death on one of Colm’s fingers.

And losing his sister, his best friend, the guy he used to look down on, and now his beloved donkey breaks something in Pádraic. Like a switch: now it’s Pádraic who wants vengeance. Now it’s Pádraic who’s coming after justice for his lost donkey. It’s not Pádraic the victim any more.

And Colm, who said that all he wanted was some peace so he could create music, has no fingers to play music with. He has inadvertently killed Jenny the donkey, and he’s feeling guilty about it. But now the real war has started.

There’s this absolutely incredible scene where Pádraic comes to Colm, in front of everybody, and says, essentially, “I’m going to burn your house down at two in the morning, and I’m not going to check to see if you’re in there. But leave the dog outside, because he’s the only nice part about you.”

On the other side of the sea change, The Banshees of Inisherin flips the same structure inside out.

We started with Colm threatening to cut off his own fingers if Pádraic doesn’t leave him alone. But there’s been a flip, now– Martin McDonagh literally ‘flipped the script’– with Colm feeling awful about killing Pádraic’s donkey and Pádraic wanting to burn his friend alive.

But that isn’t the only flip this incredible screenplay gives us. In an earlier scene, after Pádraic verbally attacked Colm at the bar, Pádraic apologizes and asks if they’re even. And Colm responds, “Why can’t you just leave me alone?” He doubles down.

On the other side of the sea change we get a flip of that scene, at the end of it all. After Pádraic has burned down Colm’s house– he looks back, sees Colm inside the house, and lets it burn. But Colm does end up getting out, and the two meet on the same beach they had that first conversation. Colm asks if they’re even, extends his hand to shake. And Pádraic says, “No. If you’d stayed in the house we’d be even. This is going to stay with us till our deaths.”

Colm and Pádraic are both mirror images of where they’d started. Pádraic just wanted to be friends. He was so desperate to be friends that he chased after a man who was being– when you think about it– very cruel to him. Now, he’s lost every relationship in his life, right down to his donkey, and he doesn’t want to be friends anymore. Now, he wants vengeance. Meanwhile, Colm, who cut Pádraic out of his life and wasn’t letting Pádraic make peace, just wants the two to be at peace again.

There’s been this giant flip in the structure of the story. And we’ve gotten to where we expected things to go– we knew this thing was going to lead to a bloodbath from that first threat, or even from the title. But we haven’t gotten there the way we expected to get there: we never expected Pádraic to be the guy who wasn’t going to want to end the war.

When you’re building an allegory like The Banshees of Inisherin– whenever you’re building a script that is much more complicated than what’s really going on in the page– your characters can’t just be metaphors: you have to build the character drama on top of the allegory.

In the same way, if you’re building an action movie, it can’t just be action: you have to build the drama on top of it. It’s always about the relationships, about the people who matter. Beyond the stunts and the fight scenes and the political commentary, you have to build in the people to build the stakes.

It’s always about people: what they want, what’s getting in the way of that, and the choices they make that take things further. How does what they– or we– fear most end up manifesting in a way that wasn’t quite how we were expecting? That’s where stakes come from. That’s where drama comes from. That’s where the structure of a screenplay comes from.

On the structural level, you can see how simple this screenplay is: it’s a bunch of reflected scenes. First, the game of the scene is I want to be your friend!/Don’t talk to me. Then it becomes, I want to be your friend!/I’m cutting off my fingers. And then there’s a flip: “I want to be your friend/I won’t stop this war until we both die”, and the characters have switched places. Structurally, it’s super simple, and it’s unbelievably compelling.

If you go back to Everything Everywhere All At Once, you’ll see exactly the same thing. The whole movie, for all its complexity, is set up in that very simple first scene in the laundromat. It’s really just a story of a girl who wants to be accepted by her mother, and a mother who is so overwhelmed by trying to control the world that she’s not hearing anyone around her. That’s the simple story that’s getting blown up with all this complexity.

So, whether you’re building a simple movie, like The Banshees of Inisherin, or whether you’re building a super complicated action movie like Everything Everywhere All At Once, you’re actually building around the same fundamental elements. You’re still just building a drama. And this is true if you’re building a silly comedy, too: you’re always building a drama.

And by that, what I mean is that you’re building a story about characters who want stuff, facing huge obstacles, making choices they’ve never made before. You’re allowing the worst possible thing to manifest, but not in the way they expect it. You’re telling a story of change.

What does The Banshees of Inisherin mean? The allegory of the Irish Civil War.

Underneath all the simplicity in this script is something much more complicated and much more profound: This is really a story about the Irish Civil War, which then led to the troubles of Ireland. Little clues about that allegory are dripped throughout this entire movie.

In the most important one of these little bits of exposition, you have Dominic’s dad, Paedar, in the bar with Colm. Paedar is a policeman, and he’s awful to Dominic and to Pádraic. Pádraic is very jealous, because Colm is talking to this total jerk of a man when he won’t even talk to Pádraic. Pádraic overhears that Paedar is extremely excited: he’s being paid a fortune to go to the mainland for an execution, just in case things get out of hand there. As Paeder puts it:

“The Free State lads are executin’ a couple of the IRA lads. Or is it the other way around? I find it hard to follow these days. Wasn’t it so much easier when we was all on the same side, and it was just the English we was killin’? I think it was. I preferred it.”

This little monologue– delivered by the worst person in the whole movie– is actually the key to understanding what Martin McDonagh is saying and the allegorical meaning of The Banshees of Inisherin.

What he’s actually saying is this.

We used to all be on the same side. We were friends, Protestants and Catholics. Even though we were unlikely friends, like Colm and Pádraic, we were friends. We were on the same side fighting the British. And we finally got what we wanted: peace. But instead of accepting peace, we started fighting among ourselves. We decided, for reasons that maybe sounded good at the time, but don’t actually make sense, that we didn’t want to be friends anymore.

We decided we’re better than them. Or they think we’re better than us. Just like Colm talking about Mozart, and how he’s he is a deep thinker trying to leave a legacy unlike that dullard Pádraic. But he doesn’t even know what year Mozart lived.

They’re all equally dull. But they’re fighting with each other for reasons they don’t even fully understand. They’ve decided they’re no longer friends. They are no longer brothers.

And their stubbornness has caused escalations between two groups who once were unified, in a place that had the potential to be idyllic. The groups that won ended up destroying themselves and each other: committing the ultimate sin. First of self-mutilation, and then of murder.

Colm claims that all of this was just because he wanted to create beautiful music that would be his legacy. But Patrick’s sister Siobhán calls him out on it: “It’s going to be really hard to do that with no fingers.” And Colm says, “Yeah. now we’re getting somewhere.”

Again, this is a clue from Martin McDonagh about what The Banshees of Inisherin is really about. What Colm claims he wants is false, even though he may believe it.

There used to be a banshee screaming: it was called “the English,” and the characters of Ireland were united against it. They were Irish, and they were friends. Protestant and Catholic, Pádraic and Colm. They might have been oddly matched, but they could have a drink together.

Sadly, the banshee’s not gone. The banshee is just like the creepy old lady Mrs. McCormack, just like the banshee that Colm talks about in his song: it isn’t screaming anymore, it’s just watching the people that it once oppressed turn on each other instead.

And where does that turn come from?

It’s a series of actions that nobody totally even recollects the how and why of. A bunch of actions that cost both sides the things that mattered to them. Pádraic’s revenge is rooted in history: one of the things that happened in the Civil War was the factions burning down each other’s houses.

This allegory is about how these two oddly matched friends turned on each other and lost their opportunity for peace, how the two sides ended up destroying both their own dreams and each other’s. Even though there’s a part of them that still knows they’re one people, and knows that they love each other, even though there are these moments of beauty, just like we have with Colm and Pádraic, hands cannot be shaken and peace cannot be made.

Thematically, The Banshees of Inisherin is a story about despair.

And the story of that despair is captured in two truly brilliant scenes, two mirrors of each other. Both of them are played for comedy, and they’re both confessions to the priest.

We see a priest come to the island, and we get the sense that he’s a priest who travels from place to place doing a service here and a service there. After the service, Pádraic whispers in the priest’s ear because he wants his help: he wants Colm to be his friend again.

Then Colm steps into the confession box.

And the priest says, “How’s the despair?”

“Not so much, of late,” says Colm. “Thanks be.”

You see, Colm thinks that by cutting out his friend, he has cut out the despair. That without Pádraic, he’s going to live this idyllic life of music. He “just doesn’t want to tango anymore,” to use his words from later in the movie.

But there are two sides in this country; it’s impossible not to tango.

The priest asks him, “Why aren’t you talking to Pádraic no more?”

And Colm calls his bluff: “That wouldn’t be a sin, now, would it, Father?”

The priest says, “It wouldn’t be a sin, no, but it’s not very nice, either… It isn’t him you have impure thoughts about, is it?”

So we’re the first part of the scene, and you can see what’s really happening here: The priest is pointing towards that question of despair. And how this whole thing is actually Colm’s attempt to make sense of his own despair, his own belief that he’s just sitting around whiling away the time till the banshees come. That maybe even his dream of music isn’t real. It’s his despair that has led him to turn on his friend and brother, and the priest is pointing towards that.

And then, because it’s Martin McDonagh, and because he’s brilliant, we get this allegorical meaning with so much subtlety we barely notice, just like he did with Jenny the donkey. We don’t get up on the soapbox; we get it buried in comedy.

“People do have impure thoughts about men, too.”

“Do you have impure thoughts about men, Father?”

“I do not have impure thoughts about men. How dare you say that about a man of the cloth?”

“Well, you started it,” says Colm.

“Well, you can get out of me confessional right now, so you can, and I’m not forgiving you any of those things until next time.”

And Colm says, “I better not be dying in the meantime, then, Father, or I’ll be pure fucked.”

So we have this wonderful scene that ends with comedy, so that we don’t feel like Martin McDonagh’s up on his soapbox telling us what to think. He just drops in this simple idea: “What about the despair?” that points towards the truth that Colm doesn’t want to look at.

It’s the same way that Siobhán points towards the truth when she says “it’s going to be really hard to make music with no fingers.”

It’s the same way that Colm speaks the truth when he talks about the banshees in his song, and about his own fear.

So, there’s that problem of despair, but then it gets buried in this wonderful scene where the priest is just being hypocritical. “You know, people have impure thoughts about men. How dare you say I have impure thoughts about men??”

When you’re writing an allegory like The Banshees of Inisherin, when you’re writing an important movie, when you’re writing a scene that’s supposed to do something for the meaning of your script, you’re always also writing a drama.

When you’re writing a comedy, you’re also writing a drama.

Drama begins with characters who want something and make specific choices that other characters wouldn’t make.

That character of the priest is what allows the scene to breathe and not feel heavy-handed. The wonderful hypocrisy of the priest who wants to open his arms to his brother who may be having impure thoughts about men, but is going to send the guy to hell if necessary for even implying he might have them. It’s a dominant trait of the character that makes him super compelling, but it– like so much else in that scene– is pointing to something else: the hypocrisy of all of these characters.

In fact, the only character who’s not showing hypocrisy is Siobhán, who needs to leave the place she loves because it’s become intolerable.

We then get another fabulous scene with the priest on the other side of the sea change. At this point, Colm has cut off all of his fingers, the donkey is dead, and Colm’s former best friend has just promised to show up and burn down his house. And Colm shows up again for confession.

“Well, all the ones from last time you didn’t forgive me for, multiplied by two, of course,” Colm says. “Definitely pride, this time.”

So you can see, in the previous scene, Colm says: “Maybe some pride, although I never saw it as a sin.” Now, “definitely pride this time.”

Comparing those two scenes you start to realize, okay, so this is about despair and pride.

The Banshees of Inisherin is looking at pride, hypocrisy, and despair in both the political allegory and the character drama.

Martin McDonagh is pointing the finger at both sides. He’s telling you that it’s the pride and hypocrisy and the despair of both sides that led to this horrible civil war and everything afterwards.

It’s Colm’s pride, that he is a wise musician leaving a legacy without that dull man taking up all his time, but it’s also Pádraic’s pride. No, he’s not the dull one. There has to be someone dimmer than him. He can’t have lost his friend. They can’t have been an odd pairing. His desire not to fall down the social ladder. They both have pride.

And just in case it’s not clear, Siobhán sends her brother a letter saying, “Hey, come live with me. There’s a job for you here. You have every opportunity to come to a place of peace.” And Pádraic is going to lie to her, and stay.

But– returning to that second scene in the confession booth– Colm continues, “I killed a miniature donkey. It was an accident, but I do feel bad about it.”

The priest says, “Do you think God gives a damn about miniature donkeys, Colm?”

And Colm says this incredible line that really helps you understand the despair underneath: “I fear he doesn’t. And I fear that’s where it’s all gone wrong.”

To me, this is a devastating line. But it also speaks to Martin McDonagh’s deeper point: We’ve forgotten this simple little thing called love. We’ve forgotten about the things that actually bring us together. This line speaks to his fear that maybe God doesn’t care.

“Is that it?” The priest says, “aren’t you forgetting a couple of things? Wouldn’t you say punching a policeman’s a sin?”

Now, we haven’t covered this yet. Colm decked a policeman, because the policeman was giving poor Pádraic a really hard time and Colm feels guilty about the death of the donkey. He wants to protect his friend, it’s just too late to actually be friends again.

Colm says, “If punching a policeman is a sin, we may as well just pack it up and go home.”

The priest says, “And self-mutilation is a sin. It’s one of the biggest.”

Colm says, “Is it? Self-mutilation? So you have me there, multiplied by five.”

You can see that Martin McDonagh is not just talking about Colm cutting off his fingers. He’s also talking about cutting off his friend. He’s talking about how the Civil War and the troubles were actually an act of self-mutilation that cost both sides. It cost both sides of the Civil War the legacy they were trying to leave, the peace, the meaning: everything that they said that they wanted.

That’s why the priest follows that up with a mirror of the same line. “How’s the despair?”

“It’s back a bit,” Colm says, sitting there with no fingers and a bleeding hand.

“But you’re not going to do anything about it.” The priest says.

“I’m not going to do anything about it. No.”

“12 Hail Marys and 11 Our Fathers,” and he’s out.

But a moment later, we see how close Colm does come to doing something about it: he almost sits in his house and lets his friend burn him alive.

We see a character who thinks he’s just taking action against himself, but he’s actually starting a war.

We see what happens when you fall into despair and pride: How a vision for peace can be destroyed. How a war against the common enemy that could have led you to this mythical island where everyone could get along, can instead turn your home into a place you have to flee.

What does The Banshees of Inisherin mean for us?

Just to get political for a moment– because we’re looking at a political movie– I think we’re at a similar place in our country. We have two sides doubling down on pride and despair. I think we’re in a place where we’re at a risk of forgetting our love for each other, and bringing ourselves to a place where our country is somewhere we may have to flee.

I think that’s one of the reasons why The Banshees of Inisherin is such a powerful film right now: it’s not just about the Irish troubles, it’s about our troubles. It’s about human troubles. Even though it’s told in what seems like a really simple, almost fairy tale form, and even though it’s dripped with comedy to make the medicine go down, it’s really a movie about despair and pride.

How those two simple ideas turn us against each other and destroy our opportunities for peace.

I hope you enjoyed this podcast. If you’re getting a lot out of it, come study with me: I have a free class every Thursday night online, called Thursday Night Writes.

If you want to take your writing further, we have an incredible program called Protrack that pairs you one-on-one with a professional writer who will meet with you. They’ll read every page you write, every draft you complete, and be your mentor throughout your entire career– for a tiny fraction of what you would pay for a single semester at film school.

In addition to that, we have a whole slate of extraordinary screenwriting classes and TV writing classes. So come check us out!